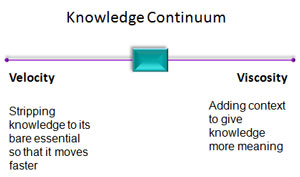

Velocity and Viscosity

Velocity — the speed with which knowledge moves through an organization.

Velocity — the speed with which knowledge moves through an organization.

Viscosity — the richness or thickness of the knowledge transferred.

Davenport and Prusak (1998) describes how knowledge is affected by the speed it moves through the organization (velocity) and the richness of how much context it has (viscosity).

The authors tell the story of how Mobil Oil's engineers developed some very sophisticated ways to determine how much steam is required to drill under certain conditions. When they applied their techniques, they found they could reduce the amount of steam they generated themselves and bought from outside sources. Since they knew the precise amount needed, the potential savings were huge. So they embedded the technique in an intelligent system, with the main focus being the knowledge's velocity in order to quickly get the information out to the field. This was done by sending a memo to all the drilling operations detailing the calculations and benefits. They assumed other sites would quickly adapt the innovation. Nothing happened. The effective velocity level was zero because the means of communicating the information (a memo) was of very low viscosity.

Simply improving a process will not be enough to win over everyone. So Mobil came up with some other techniques for transferring the knowledge, such as videos and case studies and soon raised the adoption rate to 30%. Adding the additional context provided the needed viscosity to it. It now looks as if it will grow to 50%. Will it ever reach 100%? Who knows? The resistance to abandoning processes that have been successful for years in the past is a universal phenomenon that is not just limited to Mobil.

Velocity strips knowledge and information down to its bare essentials by removing portions of its context and richness, however it does allow it to move much faster. And this stripping effect often takes the message down to the next level for its intended receivers — from knowledge to information or from information to data. Thus, the intended knowledge exchange fails.

Now look at how 3M does it — they have regular meetings and fairs for exchanging knowledge. One of their most famous products, scotch tape, was invented by Dick Drew, a sandpaper salesman. In almost any other company his idea would have been tossed out as tape and research were not his specialty, yet the culture of 3M allows for the viscosity of information to spread. . . no matter who originates the idea. And the way they ensure it spreads is through interactive meetings and knowledge fairs — it is not left for a chance happening on their intranet or through a memo.

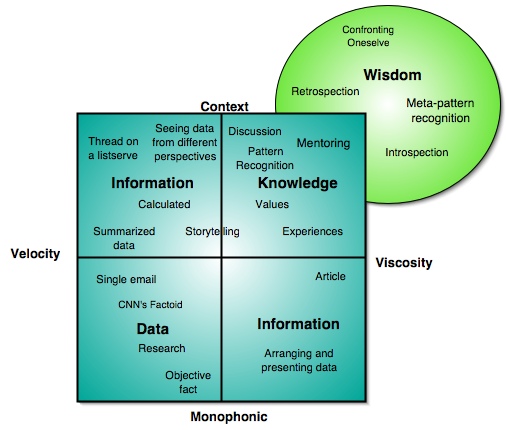

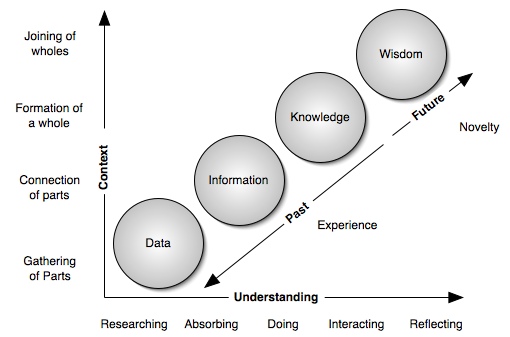

Knowledge requires rich sources and context. For example, one of the best knowledge-enablers for a beginning learner is apprenticeship as it allows a rich exchange of concepts and ideas between the learner and teacher. As one starts to slowly move away from this form of learning, the knowledge exchange slowly starts to decrease, while the rate of information flow increases. That is, in a class, the information is going out to a number of learners at once, hence the speed of information exchange increases; however, the flip-side is that as one-on-one interactions decrease, the rate of knowledge transfer decreases. This is the first dimension of the data/information/knowledge continuum—Viscosity/Velocity.

The second dimension of the data/information/knowledge continuum is the number of paths or streams of information flow. A single email (monophonic) sent to a direct report is one stream, where a list server normally has multiple posts (context) to each thread. The more posts, then the more viewpoints one can gather or harvest. This multiple stream effect can also be seen on Twitter when followers tweet their views on a single subject.

Once a learner moves past the beginner stage, then these multiple viewpoints start to become invaluable as they add context to the knowledge base that one has gained. For example, A PhD student studies one small section of his or her field, but does so from multiple contexts.

Next Step

Click on the various parts of the chart below to learn more about the topic. Or go to Performance Management to learn about other methods for increasing the flow of knowledge.

Reference

Davenport, T., Prusak, L. (1998). Working Knowledge. Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA.