John Locke - Defining Knowledge - 1689

Knowledge is the perception of the agreement or disagreement of two ideas - John Locke (1689) BOOK IV. Of Knowledge and Probability. An Essay: Concerning Human Understanding.

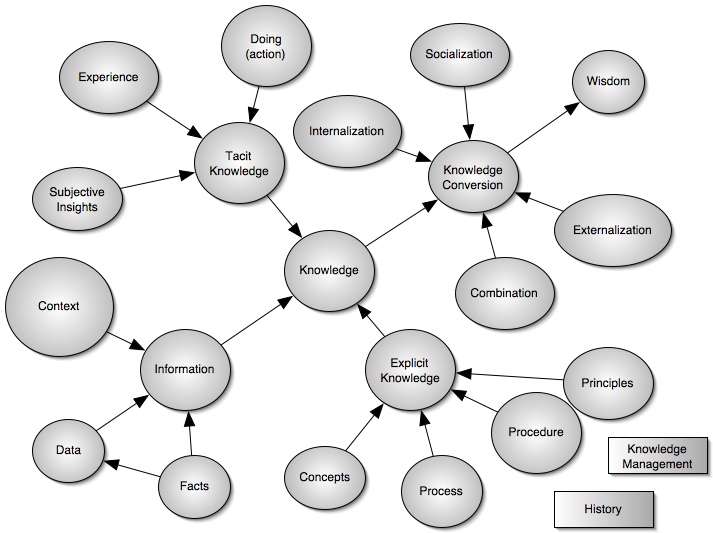

John Locke (1632-1704) gave us the first hint of what knowledge is all about. Locke views us as having sense organs that when stimulated, produce “ideas of sensation.” These ideas of sensation, in turn, are operated on by our minds to produce “ideas of reflection.” Thus, ideas come to us via our senses, which in turn can be turned into new ideas via reflection.

These two routes that ideas take are derived from experiences — we can have no knowledge beyond our ideas.

There are two kinds of material ideas: simple and complex. Simple ideas have one attribute, such as the sky is blue or lemons are sour. While complex ideas are compounds of simple ideas.

There are building blocks to ideas — they come to us via our senses, and in turn we can reflect upon them to form complex ideas.

Locke further divides knowledge into three types:

- Intuitive knowledge involves direct and immediate recognition of the agreement or disagreement of two ideas. It yields perfect certainty, but is only rarely available to us. For example, I know intuitively that a dog is not the same as an elephant.

- Demonstrative knowledge is when we perceive the agreement or disagreement indirectly through a series of intermediate ideas. For example, I know that A is greater than B and B is greater than C, thus I know demonstratively that A is greater than C.

- Sensitive knowledge is when our sensory ideas are caused by existing things even when we do not know what causes the idea within us. For example, I have know that there is something producing the odor I can smell.

Winter, McClellard, and Stewart (1981) hypothesized that a strategy of integrating ideas, courses, and disciplines would enhance critical thinking over a more typical curriculum. So they created an experimental curriculum in which the learners took a group of two or more different, but complementary subjects areas. In addition, the courses focused on integrating the different disciplines. After the study, they concluded that integrating two or more disciplines at the same time elicits greater cognitive growth than simply studying the same material in separate courses without the integrative structure.

This study is quite interesting in that it ties in directly with John Locke's idea of knowledge being two or more different concepts — and that the way you grow knowledge, or in this case critical thinking, is to allow the learners to learn more than one idea or concept at a time.

Next Step

Return to the Information and Knowledge page

Reference

Winter, D., McClellard, D., Stewart, A. (1981). A new case for the liberal arts: Assessing institutional goals and student development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.