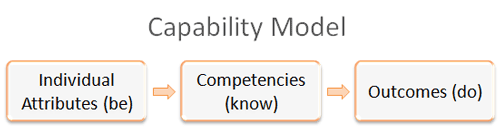

Capability Model

How do competencies, attitudes, and all the other things in our mind drive performance? Fortunately, we have the help of the U.S. Army and the Defense Department who created a human performance model in the early 1990s with a project led by Mark Mumford (Northouse, 2004). The goal was to explain the underlying elements of effective performance. The end product is known as a “capability model” (sometimes called a skill model) that frames performance as the capabilities that make effective performance possible.

How do competencies, attitudes, and all the other things in our mind drive performance? Fortunately, we have the help of the U.S. Army and the Defense Department who created a human performance model in the early 1990s with a project led by Mark Mumford (Northouse, 2004). The goal was to explain the underlying elements of effective performance. The end product is known as a “capability model” (sometimes called a skill model) that frames performance as the capabilities that make effective performance possible.

So rather than just collecting a bunch of tasks that the performer should be able to do, the model formats them out in a more manageable framework in order to gain an understanding of what exactly makes an effective performer. The model has three components: Individual Attributes, Competencies, and Outcomes that feed into each other (Northouse, 2004):

One of the reasons that attributes are kept separate from competencies, is that competencies are normally trained as they can be used immediately upon the learner returning to the job, while attributes normally fall under development in that while they help the learner to grow, they normally take longer to make a positive impact on the organization.

Individual Attributes

Individual Attributes are composed of:

-

General Cognitive Ability — This can be thought of as intelligence, which is linked to biology, rather than experience [1]. While the Army conducts general entrance exams to measure the intelligence levels of new recruits, the civilian world generally relies on other means, such as the applicant's educational level and grades to make a rough guess on the worker's intelligence [2].

-

Crystallized Cognitive Ability — This is the intellectual ability that is learned and acquired over time. In most adults, this cognitive ability continuously grows and does not normally fall unless some sort of mental disease or illness sets in. It is composed of the ideas and mental abilities that we learn through experience.

-

Motivation — This is the performer's willingness to tackle problems, exert their influence, and advance the overall human good and value of the organization.

-

Personality — These are any characteristics that help the performers to cope with complex organizational situations. Some people use the terms personality, traits, and attitudes interchangeably.

Competencies

Competencies are the heart of the model:

-

Problem-Solving Skills — These are the performers' creative abilities to solve unusual and ill-defined organizational problems.

-

Social Judgment Skills — This is the capacity to understand people and social systems. They enable the performers to work with each other.

-

Knowledge — This is the accumulation of information and the mental structures used to organize the information (schema - a mental model of a person, object or situation). Knowledge results from developing an assortment of complex schemata for learning and organizing data (knowledge structure).

Outcomes

Outcomes refers to the degree that the person has successfully performed his or her duties. It is measured by standard external criteria. Tasks basically fit in this component of the capability model; while competencies and attributes allows one to effectively perform the tasks.

The above framework will probably not fit your organization perfectly, but a little bit of tweaking should give you a basic roadmap to follow during your competency mapping project. Do not get hung up with identify basic tasks, rather than competencies (unless of course this is one of your goals). A task is normally identified with a particular job, duty, or project; while a competency is a knowledge structure and/or related skill sets that will guide a person throughout a chosen career path.

For example, if one is in the training profession, then having a good knowledge base on ADDIE will help guide the person throughout her career path, such as being a trainer, designer, consultant, or project manager. Within that competency, are basic tasks or concepts that are used in particular functions of training. For example, a learning objective is normally written by a designer, while the trainer uses it as a guide to ensure the end-results are met.In addition, a good consultant might never use the term in certain situations because she knows it will only confuse her present clients.

End Notes

. The first attribute, General Cognitive Ability, is the only one that normally remains consistently stable over a person's lifetime. However, it can be compensated for by the second attribute, Crystallized Cognitive Ability.

The majority of organizations will have no real means to distinguish between General Cognitive Ability and Crystalized Cognitive Ability since they normally only use rough measures to get some idea of a person’s intelligence level (and even these do not normally come close). Thus, you might want to combine the two together for your project. However, no matter which way you decide to go, this does gives you a place to put a person's “diploma” or other general cognitive abilities if your mapping project decides that they are needed.

Next Steps

-

-

Capability Model

Reference

McClelland, D.C. (1973). Testing for competence rather than for intelligence. American Psychologist, 28, 1-14.

Northouse, P. (2004). Leadership Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.