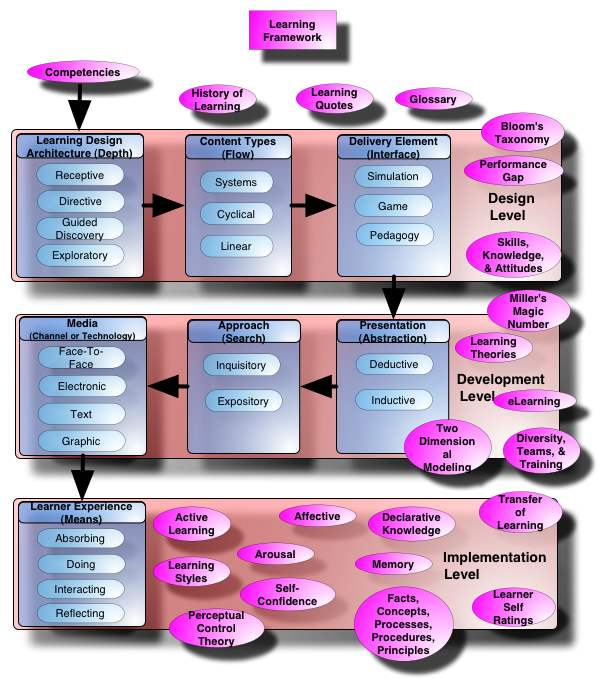

Learning Theories: The Three Representational Modes

All information that is perceived via the senses passes through three processors that encode it as linguistic, nonlinguistic, or affective representations (Marzano, 1998). This is how we learn.

For example, if you go to a football game for the first time you encode information:

-

linguistically, such as rules and customs;

-

retain mental images nonlinguistically, such as mental images of the players positioning themselves and then getting in the proper stance;

-

have various sensations that are encoded affectively, such as the excitement during a touchdown or turnover.

Each representation may be thought of as a record that is encoded and then filed away.

The Linguistic Mode

In the educational and training world, knowledge is most commonly presented linguistically (the study of language), so perhaps this mode receives the most attention from a learning standpoint (Chomsky, 1988). The linguistic mode includes verbal communication, reading, watching (e.g. learn the rule of chess through observation), etc.

Discussions and theories around the linguistic mode can get quite complex so I am keeping this fairly simple. Basically, the linguistic processor encodes our experiences as abstract propositions.

Propositions are thought to perform a number of other functions in addition to being the primary bearers of truth and falsity and the things expressed by collections of declarative sentences in virtue of which all members of the collection "say the same thing". Propositions represent the things we doubt and know. They are the bearers of modal properties, such as being necessary and possible. Some of them are the things that ought to be true.

These propositions are organized into two networks:

-

The declarative network contains information about specific events and the information generalized from them. These are the “what” of human knowledge.

-

The procedural network contains information about how to perform specific mental or physical processes, such as “IF and THEN” statements.

These two networks are the main channels for interacting with each other (communication). Communication is the main functions of language. Language symbols are used to represent things in the world. Indeed, we can even represent things that do not even exist. Communication does not imply a language, for example using hand signals. But a language does imply communication, that is, when we use language, we normally use it to communicate.

The Nonlinguistic Mode

This includes mental pictures, smell, kinesthetic, tactile, auditory, and taste. At first, we might believe that they are entirely different structures, however these representations are quite similar to each other in that these nonlinguistic sensations function in a similar fashion in permanent memory (Richardson, 1983). That is, although we sense things differently, such as smell and touch, they are stored in mental representations that are quite similar. They also lose a lot of their robustness once the experience is over and transferred to memory. For example, picturing the smell of a rose from memory is not as vivid as actually smelling a real rose.

Although we can realistically study linguistics, taste, hearing, etc.; mental images are another matter. . . how do you study a picture in someone's mind? Hence, there are several models for the nonlinguistic mode in the psychology world. However, there are a few things we know for certain:

-

Mental images can be generated from two sources - the eyes (e.g., the after image of a light bulb) and from permanent memory (using your mind to picture a tiger that has squares instead of dots).

-

Mental images are an essential aspect of nonlinguistic thought and play an important part in creativity.

-

Due to the fragmented and constructed nature of mental images, they are not always accurate pictures of whole thought as compared to prepositionally-based linguistic information. However, they can have a powerful effect on our thoughts due to their intensive and vivid nature, e.g. the power of storytelling, the images we create in our mind when reading a powerful novel, metaphors, imagination, creativity, etc.

The Affective Mode

This is our feeling, emotions, and mood (Stuss & Benson, 1983):

-

Feeling is one's internal physiological state at any given point in time.

-

Emotion is the coming together of feelings and thoughts (prepositionally-based linguistic data) that are associated with the feeling.

-

Mood is the long-term emotion or the most representative emotion over a period of time.

The affective mode can be thought of as a continuum of feelings, emotions, and ultimately moods. The end points of the continuum are pleasure and pain and we normally strive to stay on the pleasure end of it.

To view affective from a different perspective, see Bloom's Taxonomy.

Robert Plutchik (2000) theorized that each basic emotion occupies a location on a circle. Blends of two basic emotions are called dyads. Blends involving adjacent emotions in the circle are first-order dyads, blends involving emotions that are separated by one other emotion are second-order dyads, and so on. For example, love is a first-order dyad resulting from the blending of adjacent basic emotions joy and trust, while guilt is a second-order dyad involving joy and fear, which are separated by acceptance. The further away two basic emotions are, the less likely they are to mix. And if two distant emotions mix, conflict is likely. Fear and surprise are adjacent and readily blend to give rise to alarm, but joy and fear are separated by acceptance and their fusion is imperfect and the conflict that results is the source of the emotion guilt. |

Next Steps

Next chapter: Linguistic Learning Mode

Next section: Self, Metacognition, Cognition, Knowledge Systems

References

Chomsky, N. (1988). Language and the problems of knowledge: The Managua lectures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Marzano, Robert J. (1998). A Theory-Based Meta-Analysis of Research on Instruction. Mid-continent Aurora, Colorado: Regional Educational Laboratory. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED427087

Plutchik, R. (2000). Emotions in the Practice of Psychotherapy: Clinical Implications of Affect Theories. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Richardson, A. (1983). Imagery: Definitions and types. Imagery: Current theory, research, and application, A.A. Sheikh (Ed.), (pp. 3-42). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Stuss, D.T., & Benson, F.D. (1983). Emotional concomitants of psychosurgery. Neuropsychology of Human Emotion, K.M. Heilman & P. Satz (eds.), pp.111-14). New York: The Guilford Press.