Designing for Agile Learning

Agile Design captures the texture and nuance of learning

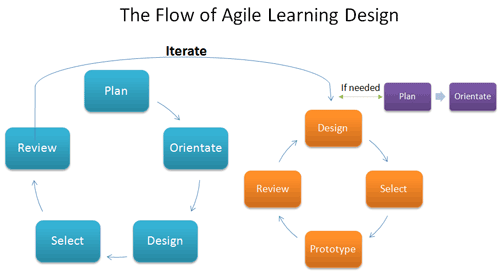

The third concept of PODSIR (Plan, Orientation, Design, Select, Iterate, Review) is Designing the Learning Process or Platform to facilitate interactions between humans, technology, and content in order to increase performance (shown in the blue cycle below).

It accomplishes “interactions” through the use of “awareness” that not only allows the content to sense and respond to the learners, such as feedback and guiding them to their next learning need; but also allowing the learners to sense and respond to the content (the term is based on Saffer's definition, 2007). During a Twitter conversation with @usable learning and @Kathysierra, “the awareness should be more like Amazon's Lists, rather than Microsoft's Clippy.”

It accomplishes “interactions” through the use of “awareness” that not only allows the content to sense and respond to the learners, such as feedback and guiding them to their next learning need; but also allowing the learners to sense and respond to the content (the term is based on Saffer's definition, 2007). During a Twitter conversation with @usable learning and @Kathysierra, “the awareness should be more like Amazon's Lists, rather than Microsoft's Clippy.”

Almost anyone can produce content but it takes a good Learning Designer to add awareness. Saffer (2007, p4) defined this awareness as the product (in this case the learning process or platform) being able to sense and respond to the learner.

It is also contextual in that it facilitates specific performance problems under a specific set of circumstances — a solution may not work for a similar problem. The end goal is to produce adaptive, agile thinkers, competent to perform within a dynamic working environment (Markley, 2006). While Learning Design is art, it is also science.

Agile Learning Design does not align itself with any one medium or technology; rather it is only concerned with the correct technology that aids in a learning and performance solution. Thus, it might be compared to distributed Learning (dL) that relies primarily on indirect communication between learners and instructors that allows the learners to learn at different times, at their own pace, as well as in different places. The old acronym was “DL”, however, this emphasized delivery method and learning equally, thus the correct acronym is now “dL”, which emphasizes learning without focus on delivery (Markley, 2006). That is, it uses face-to-face instruction when it makes sense.

Techniques to Learning Design

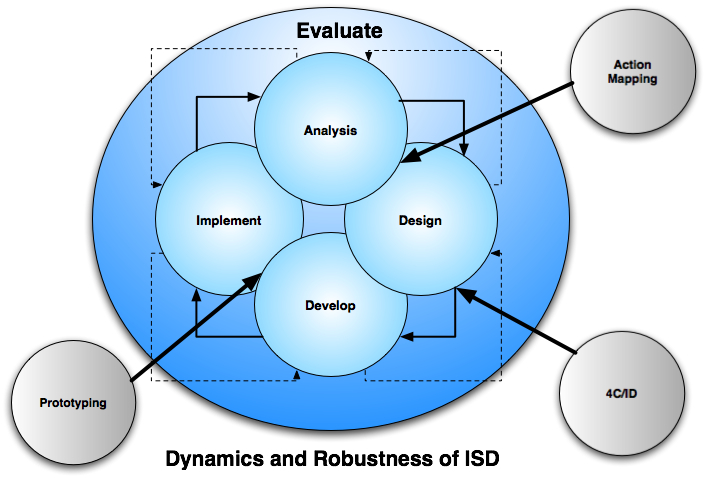

While there are specific methodologies for creating learning or instructional design, such as ISD, ADDIE, and van Merriënboer's 4C/ID Model; there are five design lenses or techniques that provide a means for viewing the overall structure of a specific learning design:

1. Performance-Centered Design

Focuses on the tasks that are composed of actions and decisions that the learners need to perform. A Learning Designer uses an Exemplary Performer as a model and then they build the instructional content and add awareness to it.

2. Guru Design

Focuses on the skills and knowledge of experts (SMEs), in which the designer may or may not be the guru. A Learning Designer uses one or more SMEs as knowledge sources and then together, they build the instructional content and add awareness to it.

3. Learner-Centered Design

Focuses on the needs and goals of the learners who guide the design; while the Learning Designer aids with the content and awareness. This is somewhat similar to user-centered design that is based on the concept that the people who use a product or service know what their needs, preferences, and goals are, thus they and the Learning Designer collaborate throughout every stage of the Agile Design process to build the content and awareness.

It should be noted that the vast majority of so called “Learner-Centered Designs” are based on the other four design techniques because they are focused on what others think the needs and goals of the learners should be, NOT what the learners think they should be.

4. System Design

System Design focuses on the system's inputs, outputs, processes, feedback loops, goals, etc. to guide the design.

5. Specialty Designs (subset)

This includes ADDIE, which is a combination of Performance, Guru, and System Design, but normally little or no Learner-Centered Design (not because the model won't let you, but because designers fail to do so). It also includes the micro-instructional designs, such a van Merriënboer's 4C/ID Model that focuses on complex task specific skills.

“The answer is, there's an infinite number of answers.” - Amanda Palmer of the Dresden Dolls

Almost no Learning Design project is accomplished through just one of the five approaches, but rather a blend, with one of them normally being the primary approach to design. For example, a Learner-Centered Design might perform a System Design and call on experts or gurus to help with the design; while a Performance Design might include some System Design, in addition to using Merriënboer's 4C/ID for higher order tasks.

So just as you can plug and play different tools or methods into ISD, you also plug these tools into Agile Learning Design so that rather than working with a tool box that only contains a couple of hammers, you work with a full set of tools that compliments the learning platform in order for the learners to fast-track and master the performance.

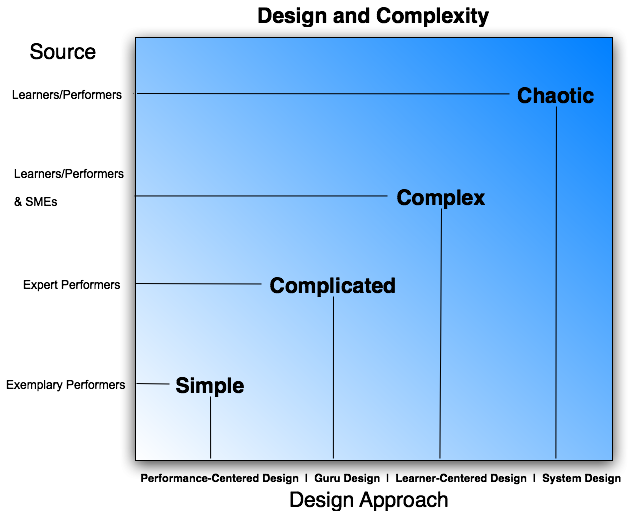

Learning Design Approaches and Orientation

The source of where you get the content, such as exemplary performers, expert performers, and SMEs (discussed in the orientation chapter), clues you in to the level of complexity of the design environment, which in turn tells you the primary design approach:

-

Exemplary Performers + Simple Environment = Performance-Centered Design

-

Expert Performers + Complicated Environment = Guru Design

-

SMEs & Learners/Performers + Complex Environment = Learner-Centered Design

-

Learners/performers and managers + Chaotic Environment = System Design

This can be pictured as:

Being able to locate the correct level of complexity of the environment tells you the main design approach to take:

Simple Design Environment — Sense-Categorize-Respond

Sense by using a collaborative process to create shared awareness and understanding of each team member's perspectives in order to create a mental model of the learning problem so that the correct decision-making can be performed.

You know you are in a simple learning design environment when you have Exemplary Performers who can role model the required performance while you observe and categorize their performance into tasks, skills, knowledge, and performance steps.

You respond by applying best practices, such as backwards planning and Action Mapping.

Complicated Design Environment — Sense-Analyze-Respond

Sense by using a collaborative process to create shared awareness and understanding of each team member's perspectives in order to create a mental model of the learning problem so that the correct decision-making can be made.

A complicated learning design environment is similar to a simple learning design environment except rather than having Exemplary Performers who you observe, you have SMEs (Subject Matter Experts), who you interview and ask questions in order to analyze their responses.

You then respond by discovering patterns in their responses and transforming the information into good practices. And normally the only way to determine if it is indeed a good practice is through a series of iterations. Thus, while a simple environment will normally only require a couple of iterations, a complicated environment will require several more.

Complex Design Environment — Probe-Sense-Respond

Since there are no Exemplary Performers to observe or SMEs to interview, the relationship between cause and effect can only be perceived in retrospect, thus the approach is to probe through deep collaboration among the learners, managers, and designers, such as telling stories about what they are experiencing (narratives).

It is often helpful to look at the system and processes by starting with the output and working backwards through them in order see what to discuss (collaborate) and if it will help with the solution. Thus, the primary design approach is Learner-Centered with the learners fulfilling the roles of SMEs, with perhaps some experts or System Designers joining in. In addition, you can use a process similar to the method Joe Deegan describes in his blog post, Project Based Learning in 3 Steps.

This probing effect should start to paint a picture or pattern that allows you to sense an “emergent practice” that can be responded to by designing and then implementing a solution based on the observed pattern. Since this will be a new practice, it will more than likely have to go though several rounds of iterations to arrive at the emergent practice.

Chaotic Design Environment — Act-Sense-Respond

Since there is no relationship between cause and effect that the team (learners, managers, and designers) can agree upon, you will need to look at the system and processes by starting with the output and working backwards in order see what you can act upon. This might seem similar to a Complex Environment, but with a Chaotic Environment you are taking guesses of what to do (perhaps educated ones), while with a Complex Environment you are seeing patterns and getting an “Aha!” moment — “this should work!”

Once the change has been implemented, sense the environment again and see if the team can now agree upon the correct level of complexity. If not, repeat the process with a new “act” until an agreement can be made.

By forcing changes into the chaotic environment, you eventually push it into one of the other three domains. At this point a pattern should emerge that will allow the team to correctly identify the environment (more than likely a Complex Environment), thus you can now respond with one of the above three approaches.

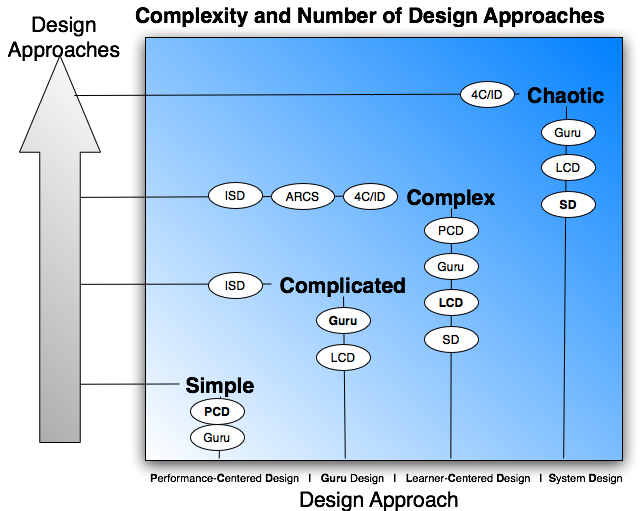

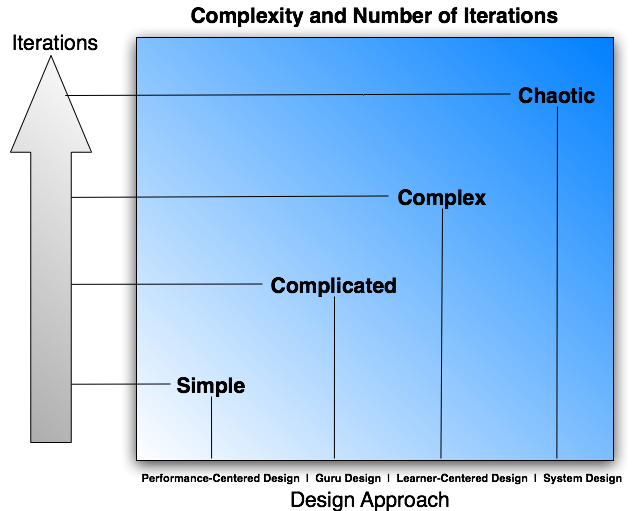

The Complexity of Design Approaches

Knowing which design environment you are in helps with the planning by, 1) informing you of the number of design approaches that will be involved, and 2) estimating the number of iterations that will be needed.

1. As the level of complexity increases, the number of design approaches to solve the problem correspondingly increases; however, there will normally be one major design approach. This will give you an idea of the scope of the design solution that you will be working in:

2. As the level of complexity increases, the number of iterations to reach a good-enough level correspondingly increases. This will give you an idea of the number of iterations that will be needed:

Next Steps

-

Design

References

Markley, J., (2006). The Army Distributed Learning Program. Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC): presentation given at the U.S. Army Courseware Conference. Retrieved from: http://wow.tradoc.army.mil/tadlp/presentations/dlcwconf06.pp3

Saffer, D., 2007. Designing for Interaction. Berkeley, CA: New Riders.