The Hype of Informal Learning

New concepts and technology always seem to bring a certain amount of hype — videos, elearning, social media —and informal learning are no exception. While informal learning is a valuable and useful concept, this section will dispel some of the myths that come along with it.

Percentage of Learning

Proponents of informal learning will often raise the percentage that informal learning accounts for to 80 or 90 percent. I have even seen one that reported that informal leaning accounts for 95% of all learning.

This is because they normally base it on extremely small surveys given to highly creative organizations, such as advertising agencies. Both Cofer (2000) and Dobbs (2000) report that the best researched numbers are the ones that report 70 percent of learning is informal while 30 percent is formal. Thus 70/30 is the average.

In fact, one survey reported even lower numbers, and the organization behind it is a big supporter of informal learning. A Chief Learning Officer survey (2007) reports that 58% of the learning occurring in organizations is informal. The editors seemed to be taken by surprise at the low numbers, but it could be explained by the organizations it surveyed. Companies that rely on a lot of set-processes to ensure their product or service meets a certain level of quality will often have a higher level of formal learning. Thus, the 70/30 ratio is an average, and depending on the organization, the numbers could differ greatly from this average.

Making Formal Learning Look Bad

One method of making you look better is by going the political route — making the other guy look bad. And while we certainly need to support informal learning as noted earlier, we should not try to do it by making false accusations against formal learning.

Some of the put downs used are witty sayings, for example, “Training is something you do to someone. Learning is something people do for themselves.”

Training is NOT something you do to others. For example, some of the roughest, toughest, but most professional people in the training business are U.S. Marine Drill Sergeants. One of their mottos is that they will not give up un a new recruit as long as he or she does not give up on themselves. Even though their training is one of the best in the world, it is not a one-size-fit-all solution, and they realize they can't do it to others; but rather the learners must be willing to learn it themselves. They adjust as long as the learners are willing to learn. I cannot do it to you; you must be willing to learn yourself.

Another ploy is using bad research. One author (Georgenson, 1982) writing for a training magazine pens a rhetorical question:

“How many times have you heard training directors say: I need to find a way to assure that what I teach in the classroom is effectively used on the job? I would estimate that only 10 percent of content which is presented in the classroom is reflected in behavioral change on the job.”

Shortly after his article appeared, a peer-reviewed journal cites the “rhetorical question” as “research has shown that only 10% of training transfer to the job” (Baldwin, Ford, 1988). Not too long after that books and speakers are citing the peer-reviewed article (and each other) as proof that training does not work. For more on this 10% training transfer myth see this article.

To add to this argument, proponents will add that not only does it not transfer, but we cannot measure it. This comes from another inaccurate piece of research. A psychology research project reported that Kirkpatrick's Four-Levels of Evaluation is not effective for evaluating training (Alliger, Janak, 1989; Horton, 1996). However, rather than actually examining real training programs, they exam a variety of formal learning programs, such as spirit-building, inculcation of company history or philosophy, and individual growth.

And of course the Four-Levels prove ineffective for evaluating these types of learning programs. The informal learning community is happy — the fake research has not only shown that training does not transfer, but also that our methods for evaluations are ineffective. However, Kirkpatrick never said that his method was valid for evaluating all learning programs, but rather just training programs.

Complexity

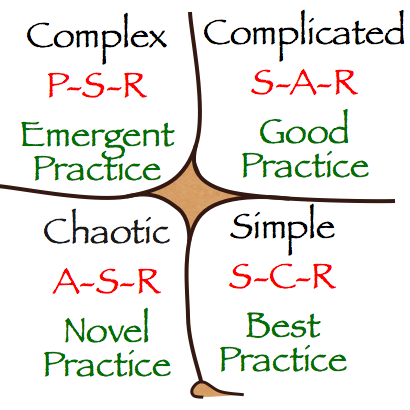

There has been some discussion recently that as the world gets more complex, formal learning becomes less relevant. By complex, I'm referring to Dave Snowden's (2000) Cynefin framework:

For more on the Cynefin framework see the section, Orientation in the Agile Design Environment in Agile Learning Design.

However, complex environments imply an emerging practice, which in turn, implies a customary way of operation or performance. Yes, they may be still emerging, but unless these emerging practices are dealt with in a manner that ensure they do indeed become a customary way of doing things, they will soon turn to chaos if left to chance.

For example, I used to work in a manufacturing environment in which our products had a relative firm foothold in our section of the food industry — mostly because it was new. Thus, with very little competition we could take our sweet time in how we dealt with growth and moving forward. However, as we became more successful, other companies, both large and small, soon moved into the same niche.

Thus in order to stay ahead of them we had to produce faster, cheaper, and with more variety; all while still maintaining the quality that our products were known for. Almost every other month we were moving onto something new, such as Lean and Just-in-Time on the manufacturing side and engagement and communication theories on the Organizational Development side in order to ward off the increasing intense competition. Basically, we would first embrace the entire concept for a short while, and then examine what worked best for us, and what had little or negative impacts, and then shed the unworthy ones.

All of this required some sort of formal learning so that we could produce quality products consistently. This process worked similar to Boyd's OODA Loop:

- Observe — What best or emerging practice can best help us?

- Orient — Test it out to get the proper context.

- Decide — What parts work best? Shed the mediocre.

- Act — Establish it as a practice, normally with the help of both formal and informal learning.

Of course, the training we provided had to be created and implemented rapidly and was often done with small chunks of learning. Anything less would only lead to chaos.

Next Steps

-

The Hype of Informal Learning

Informal and Formal Learning are part of the Periodic Table of Agile Learning:

References

Alliger, G., Janak, E. (1989). Kirkpatrick's Levels of Training Criteria: Thirty Years Later. Personnel Psychology, Summer, Vol 42 No 2: 331-342.

Baldwin, T.T., Ford, J.K. (1988). Transfer of training: A review and directions for future research. Personnel Psychology, Vol. 41(1): 63-105.

Chief Learning Officer (2007). 2007 Business Intelligence Industry Report: Executive Summary. Business Intelligence Board survey, report Num. BZ_2007_Summary_r2.qxd. Retrieved May 1, 2007 from: http://www.learningdirectorsnetwork.com/newsdocs/Business_Intelligence_Rep_2007_CLO.pdf

Cofer, D. (2000). Informal Workplace Learning. Practice Application Brief. NO 10. U.S. Department of Education: Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education.

Dobbs, K. (2000). Simple Moments of Learning. Training 35, no. 1: 52-58.

Georgenson, D. L. (1982). The Problem of Transfer Calls for Partnership. Training & Development Journal. Oct 82, Vol. 36, Issue 10, p75.

Horton, E. (1996). The Flawed Four-Level Evaluation Model. Human Resource Development Quarterly. Vol.7, No.1: 5-21.

Snowden, D. (2000). Cynefin: A sense of time and space, the social ecology of knowledge management. Knowledge Horizons: The Present and the Promise of Knowledge Management. Despres and Chauvel (eds). Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, 237-265.