Needs Assessments in Instructional Design

St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral, located in Seattle, Washington, has a circular, 40-foot labyrinth. Visitors walk the path for its centuries-old spiritual and healing properties that are steeped in tradition and symbolism. The contemplative nature of the labyrinth is said to bring inner peace by helping one to center on the spiritual nature of things, rather than the clutter of the world.

Labyrinths have been used as meditative tools as far back as the 13th century. But nowadays, walking labyrinths has evolved beyond the church, as hospitals, retreat centers, prisons, and schools are offering similar labyrinth walks to help calm people's minds by absorbing them in where they are going, while at the same time, making them aware that they do not really know where they are.

Learning Needs Assessments (LNA) or Training Needs Assessments (TNA) share several similarities with the labyrinth. Just as a labyrinth has a path to follow, the LNA has a “gap” that must be found and bridged. This gap is what is between what is currently in place and what is needed, both now and in the future. While some labyrinths have one path that must strictly be followed, others have a multitude of ways to reach the end or exit. The Performance Need Assessment is like this second group, as there is normally more that one way to bridge the gap.

While following the path of a labyrinth brings one inner-peace, building the bridge across a performance gap allows designers to have inner-peace by knowing that they can visualize an appropriate learning and performance structure.

Definition

A Training Needs Assessment is the study done in order to design and develop appropriate instructional and informational programs and material (Rossett, 1987; Rossett, Sheldon, 2001). However, it works better if you think of it as a Learning Needs Assessment so that you consider both formal and informal learning needs. That is, what do they need to learn and how can you best support their informal learning needs?

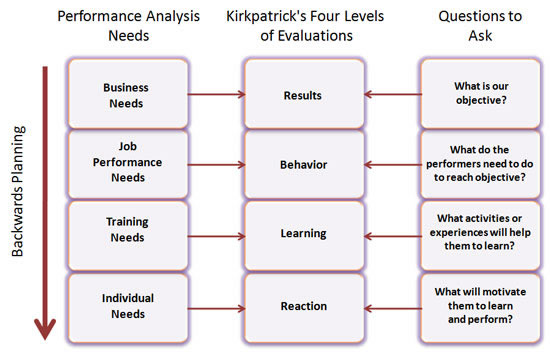

In the Backwards Planning model shown below, the first step in the Analysis phase, Business Outcome, identified the Business Need, the second step, Performance Analysis, identified the performance that is needed to obtain that objective, while this step identifies the various Learning and Training Needs and the activities and experiences they need to learn the required skills:

In addition to helping you identify the various learning needs required to obtain the desired performance, this step also allows the customer to understand the learning/training activity and its purpose. Customers often view outside activities as meddlers who interrupt their daily flow of work. These clients are often on the defensive and hide their true feelings and facts. During this initial analysis you must bring the customers in on the learning design activities and make them part of the solution. It is universally advised that the clients or customers of a proposed initiative be extensively involved in the construction of any new project (Bowsher, 1998, pp.64-88; Trolley, 2006; Wick, Pollock, Jefferson, Flanagan, 2006).

Besides introducing the customers and the training activity to each other, other benefits include that the customers will accept and benefit from a system that they themselves helped to define. In addition, nobody knows the system's learning requirements better than the people who own and work in it... often with the help of your guidance.

Exemplary Performer, Subject Matter Experts, Expert Performers, and Those Affected

There is a simple indicator that will help to identify the complexity of the problem you are facing — the source of your information. First, there are four types of experts from who you can obtain information:

-

Exemplary Performers are able to perform the tasks and are worthy of imitation, but do not have a great deal of knowledge about the peripherals surrounding the subject or task.

-

Subject Matter Experts (SME) know the subject or task, but do not presently perform in that area. An example is a college professor that teaches business, but is not engaged in a business; or a person that has performed in the subject area in the past in a wide variety of contexts, but is not presently a performer in that area.

-

Expert Performers are able to perform the tasks for a certain subject area and are worthy of imitation; in addition they have a great deal of knowledge about the peripherals surrounding the subject or task. An example is a physician assistant (PA) who works in that job during the day and teaches college courses about it at night, or a PA who not only performs the duties, but has performed in a number of surrounding areas that gives him or her a broad context of the subject and tasks. Basically, an expert performer is both a SME and Exemplary Performer.

-

Those Affected by the performance problem are often the best experts with the knowledge for solving wicked problems when then are no other experts (Rittel, 1972). This is because they live in the problem environment. Yet, the only time we normally bring them in is to be guinea pigs for testing a performance solution. Normally you will not be able to bring the entire population of them in, but do bring in enough of the population who can actually represent the population as a whole.

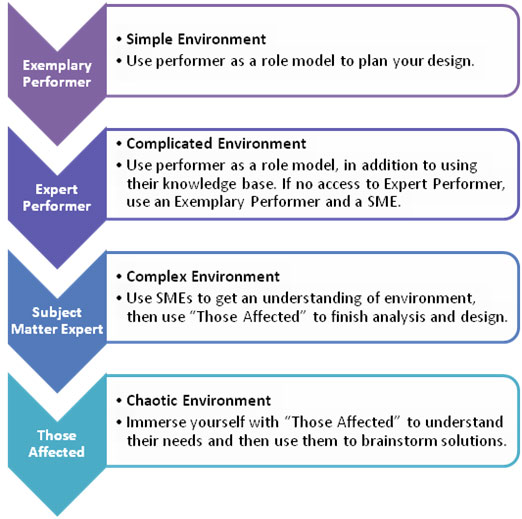

These definitions of the various experts that learning and instructional designers call upon are the keys for identifying the complexity of the design environment:

Correctly identifying your source of information helps to identify the analysis and design approach.

The experts who are sent to help you with the learning project are often the ones who have developed band-aids that keep the system running. This is not a put down, but rather a compliment. For without them the entire system would have collapsed into absolute chaos.

These people often become frustrated with the pace of the analysis process, not understanding why development of the project cannot begin immediately. They often jump ahead to design and development far too soon. Ensure you capture their suggestions in the form of design notes attached to the analysis documents for later consideration. This allows team members to feel their inputs are considered important and will not be forgotten.

Hints for Discovering Training and Learning Needs

When looking for learning and training needs, or when problems arise, there are several instruments that may be used to locate the actual symptoms:

- Immersion: Work with the employees to gain an understanding of the challenges and opportunities they face on a daily basis.

- Literature research: Analyze budget documents, quality control documents, goal statements, evaluation reports, scheduling and staffing reports, or other documents for existing problems.

- Interviews: Talk to supervisors, managers, Subject Matter Experts (SME), and employees who perform the tasks.

- Observations: Watch the job, process, or task being performed.

- Surveys: Send out written questioners.

- Group discussions: Lead a group discussion composed of employees and their managers.

Some questions that might be asked to determine training needs are:

- What are your employees doing that they shouldn't be doing?

- What specific things would you like to see your people do, but don't?

- When you envision workers performing this job properly, what do you see them doing?

- What prevents you from performing a prescribed task to standards?

- Are job aids available and if so, are they accurate? Are they being used?

- Are the standards reasonable? If not, why?

- If you could change one thing in the way you perform your work, what would it be?

- What task would you like to see your workers trained on? What would you like to be trained on?

- What new technology would benefit you the most in the performance of your work?

- What new technology would you like to see invented to help you with your work? Why?

Regardless of which method you choose and what questions you ask, the data gathered must accurately reflect the specific tasks now being performed. The information gathered will be used as the basis to select the tasks that need to be trained.

The beginning of performance is knowing what constitutes great performance. The key word is “great.” If we ask for mediocre performance, then that is what we will get . . . and you cannot pounce on the competition with something mediocre and expect to win.

Proactive or Reactive?

There are two main methods to discover learning needs. The first method takes the proactive approach. This is when a training or learning analyst studies the system or process and searches for problems, potential problems, and ways to improve it.

The goal is to make the system more effective and efficient and to prevent future problems from occurring. When a new employee is needed, the required Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes (KSA) of the candidate are known, and the KSAs the candidate must learn are also known.

The second method is when a manager comes to the Learning Department for help in fixing a problem (Reactive). These problems are usually caused by new hires, promotions, transfers, appraisals, rapid expansion, or changes, such as the introduction of new technologies. Learning departments must act rapidly when problems arise that might require a training solution. The lifeblood of the business could depend on it. First, investigate the problem. A training need exists when an employee lacks the knowledge or skill to perform an assigned task satisfactorily. It arises when there is a variation between what the employee is expected to do on the job and what the actual job performance is.

Next Steps

Go to the next section: Compile Job and Task Inventory

Return to the Table of Contents

Analysis Templates (contains several analysis templates)

Pages in the Analysis Phase:

-

Needs Assessment

References

Bowsher, J. (1998). Revolutionizing Workforce Performance: A System Approach to Mastery. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Laird, D. (1985). Approaches To Training And Development (2nd ed). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Rittel, H. (1972). On the planning crisis: systems analysis of the “first and second generation.” Bedriftsokonomen. No. 8, pp.390-396.

Rossett, A. (1987). Training Needs Assessment. Englewoods Cliff, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Rossett, A., Sheldon, K. (2001). Beyond the Podium: Delivering Training and Performance to a Digital World. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer, p.67.

Trolley, E. (2006). Lies About Learning. Israelite, L. (ed). Baltimore, Maryland: ASTD.

Wick, C., Pollock, R., Jefferson, A., Flanagan, R., (2006). The Six Disciplines of Breakthrough Learning: How to Turn Training and Development Into Business Results. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.