Leadership and Direction

Directional skills, such as making goals and plans and then solving problems as they arise are imperative as they allow you to guide your organization toward the future. These skills become even more important with the passage of time as our global environment is becoming more volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA).

Before you can guide your organization to greatness, you have to have a vision and then be able to execute it. The following tools and processes will aid you in your journey.

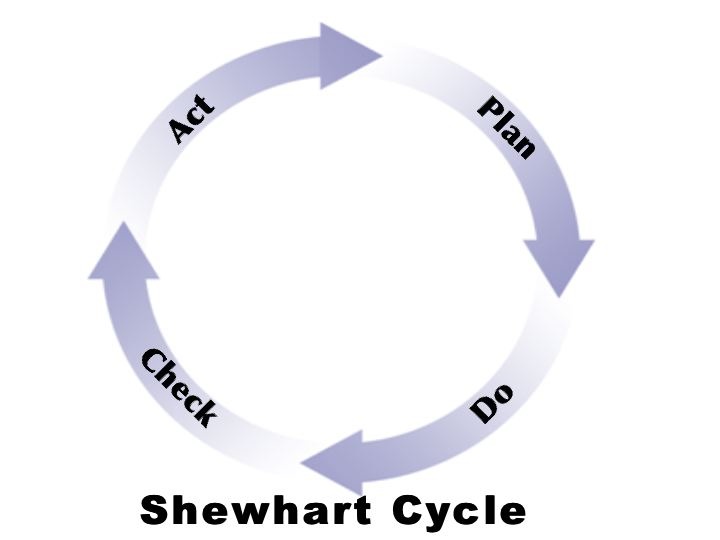

Plan, Do, Check, and Act

The PDCA cycle (Plan, Do, Check, Act) was developed by Dr. Walter Shewhart as a plan of action for creating processes and products. It is a four-step method that uses direction and control to execute, while also providing an iterative process for continuous improvement:

It is often called the Shewhart Cycle or Deming wheel. While the four steps of the cycle look easy, it actually takes a lot of work by all team members to complete the cycle correctly.

One of Shewhart's students, W. Edwards Deming later used it extensively, thus the PDCA cycle is often known as the Deming Wheel (Smith, Hawkins, 2004). Deming used a modified version — PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) as he believed study (analysis) provided a better description than check.

A dream is just a dream. A goal is a dream with a plan and a deadline. And that goal will remain a dream unless you create and execute a plan of action to accomplish it. Every goal that gets accomplished has a good plan behind of it. — Harvey Mackay

Plan

Good plans start with a brainstorming session that includes all the people involved with the project. This allows everyone to be part of the solution, in addition to gathering the best ideas.

Two key questions must be asked when planning (Army Handbook, 1973):

- What are all the ingredients necessary for its successful execution?

- What are all the possible forces or events that could hinder or destroy it?

As much as possible, get all the answers to these questions. Listen carefully to the judgment of your team. Then plan the positive forces and events, and then take action to prevent any obstructions that might hinder the project.

A detailed plan normally includes the who, what, when, where, how, and why:

- Who does it involve and who will do what?

- What are we going to do? What will happen if we do not do it?

- When does it start and end?

- Where will it take place?

- How will it take place?

- Why must we do it?

Also, the plan must be organized. Organizing is the process of creating and maintaining the conditions for effectively executing plans. It involves systematically defining and arranging each task with respect to the achievement of the objective. It includes three major steps:

- Determine all tasks

- Set up a structure to accomplish all tasks

- Allocate resources

All essential information must be brought out. It is also important to consider timing—when each task must be started and completed. A helpful approach is to use “backward planning.” Look at each goal and decide what must be done to reach it. In this way you plan from the moment of the project ending point and then work your way back to the present in order to determine what must be accomplished for each condition.

I have an example of a backwards planning model for increasing the performance of your workers. While it is about Instructional System Design, the example is fairly straight-forward in that most readers should easily understand.

Backward planning simply means looking at the big picture first, and then planning all tasks, conditions, and details in a logical sequence to make the big picture happen. Include all the details of support, time schedule, equipment, coordination, and required checks. Your team must try to think of every possible situation that will help or hinder the project. Once the process of mentally building the project has begun, the activities will come easily to mind.

Now, organize all these details into categories, such as needs, supplies, support, equipment, coordination, major tasks, etc. List all the details under the categories. Create a to-do list for each category. This list will become the checklist to ensure everything is progressing as planned.

Do

Your team cannot do everything at once; some tasks are more important than others while others have to be accomplished before another task can begin. Set priorities for each checkpoint and assign someone to perform each task on the list. Develop a system for checking each other and ensuring that each task is accomplished on time.

Plan for obtaining all the required resources and allocate them out. Not having the required resources can stop a project dead in its tracks. For this reason, you must closely track and monitor costly or hard to get resources.

Trial the plan through a prototype (experimental scale). This allows you to actually check the plan on a small scale.

Check or Study

Throughout the project's execution there are three things that you must be involved in: standards, performance, and adjustments.

The standard means, “is this project being completed or accomplished as planned? Are all the check marks being completed as stated in the planning process? The standard, which is set, must mean the same to you and your people.

Performance is measured by completing the tasks and objectives correctly. While the standard relates to the project, performance relates to the people working on the project.

If performance does not meet standards, then adjustments can be made in two ways—improve the performance or lower the standards. Most of the time, improving the performance is the appropriate choice. However, a leader may face a situation where the standard is unrealistic or costly, which means it may be lowered. This is usually caused by poor estimates or the inability to obtain the proper resources.

Act

Now you are ready to execute the plan. If your plans are solid, things will go smoothly. If your plans are faulty, then you might have a very long and hard project ahead of you!

OODA

Another similar process that can be used for planning is the OODA Cycle: Observation, Orientation, Decision, and Action.

Problem Solving

There are seven basics steps to problem solving (Butler, Gillian, Hope, 1996):

- Identify the problem: You cannot solve something if you do not know what the problem is. Ensure you have identified the real problem, not an effect of another problem. One method is the "five why's." You ask why five times. By the time you get to the fifth why, you should have found the ultimate cause of the problem.

- Gather information: Investigate the problem and uncover any other hidden effects that the problem may have caused.

- Develop courses of action: Notice that courses is plural. For every problem there are usually several possible courses of action. Identify as many as you can. There are always at least two: fix it or don't fix it. Brainstorming with your team will normally generate the most and best courses of action.

- Analyze and compare courses of action: Rank the courses of action as to their effectiveness. Some actions may fix other problems, while others may cause new problems.

- Make a decision: Select the best course of action to take.

- Make a plan: Use the planning tool covered in the first part of the section.

- Implement the plan: Take the steps to put the plan into action.

The Problem with Problem Solving Techniques

Problem solving is simply a method of fighting fires; it normally does not move the organization forward and it does not create iPads, Google, paper drinking cups made of recycled paper, or Halo 2s. Of course during the actual building of these great products, problem solving is indeed required.

Yet, how many problems really require that you follow any of these methods? Some problems you simply see and then solve — they do not require elaborate methodologies. I have even see some problems solve themselves: you forget about it, go back to it, and it is gone. On the other hand, these problem solving methodologies are sometimes too simple for complicated problems. The ability to solve problems is normally based on a person's skill-set, rather than on a heuristic procedure.

That is, the real key to solving novel problems is often a deeper conceptual understanding of the target domain. For example, neither of the above two problem solving techniques will help non-engineers solve an engineering problem when it comes to building a bridge as they do not have the basic concepts. And in turn, many problem solving techniques will not help an expert engineer when it comes to solving a bridge building problem as the models are too simplistic in nature to be of much help.

In addition, these problem solving techniques can often be misleading to novices. Novices think that by following the heuristic, they will arrive at the correct solution; however, difficult problems often require a trial and error method. Novices will often stubbornly stick to a failing solution, whereas experts with deep conceptual understandings will quickly see that a solution is not working and respond with a new procedure. Their problem solving has everything to do with adaptability and deep knowledge structures and nothing to do with the simple problem solving methods described above.

Thus, when using any problem solving technique, realize that they all have limitations and the two most useful tools are brainstorming and learning all you can about the problem at hand in order to gain a deeper conceptual understanding.

Next Steps

Next chapter: Leadership Models

References

Butler, G., Hope, T. (1996). Managing Your Mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Deming, W.E. (1986). Out of the Crisis. MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study.

Shewhart, W.A. (1939). Statistical Method from the Viewpoint of Quality Control. New York: Dover.

Smith, R., Hawkins, B. (2004). Lean Maintenance: Reduce Costs, Improve Quality, and Increase Market Share. Burlington, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

U.S. Army Handbook (1973). Military Leadership. Ft. Monroe, VA: HQ TRADOC.